This is an uncorrected chapter of a book I’m working on provisionally titled Live From California: The ’60s — Before, During, and After — 1935-1973.

It’s sort of an autobiography of my first 38 years, which includes my observations on the ’60s. Having grown up in San Francisco, going to Lowell, which was the edge of the Haight-Ashbury district, having dropped out of the straight world in 1965, I have a different take on what went on in these few years, before everything — at least in the Haight district — fell apart.

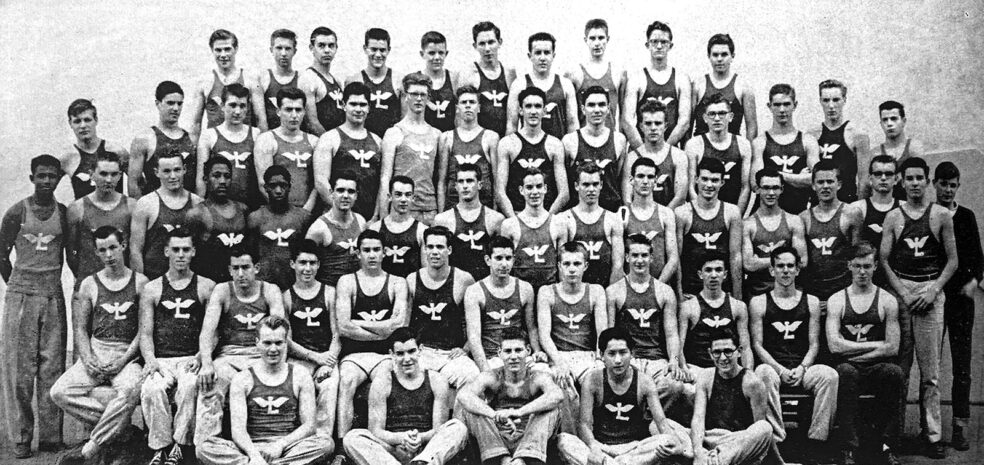

Lowell, class of 1952. There were about 250 of us.

Note the eight or so of us facing each other — not the camera — in the second row down from the top. (Click or hover over the image for a zoomed detail.)

Lowell was the one high school in San Francisco you could attend, regardless of what district you lived in. It was one of the best high schools in the country and many graduates went on to Stanford or Cal (UC Berkeley).

(Interestingly, Lowell was the subject of a New Yorker article titled What Happens When an Elite Public School Becomes Open to All in March, 2022. There was no test required to get into Lowell in my day, but in intervening years, demand to attend was so great that testing was required and this became a controversial issue — too much to cover here.)

I had skipped 5th grade,* so was a year younger than my classmates. I didn’t know many kids there when I started; most of them were from different parts of the city. For the first two years I hung out with a few kids, and had a steady girlfriend, Cora Mae Bolles.

I had skipped 5th grade,* so was a year younger than my classmates. I didn’t know many kids there when I started; most of them were from different parts of the city. For the first two years I hung out with a few kids, and had a steady girlfriend, Cora Mae Bolles.*Mrs. Wasp, my fifth grade teacher told me I should study to be a lawyer, I guess because I argued so much.

Teachers

My two favorite teachers were Mrs. Cooper, who encouraged me to write, and Jack Patterson, the journalism teacher. Years later, at a reunion, three of us discovered we were in our present occupations (English teacher, staff the San Francisco Examiner, and publisher) — largely due to “Captain Jack.”

Patterson had been a captain in the Marines and had a Silver Star from World War II. He was small and wiry, bald, and had piercing blue eyes that twinkled with humor and mischief. It turned out he was gay, although he never came on to us.

He was a great teacher. I remember to this day how he described the “five w’s and one h” of journalism that, he said, should be in the first paragraph of every news story: who, what, where, when, why, and how.

And how a journalist’s duty was to report objectively (as far as that was possible). Opinion was for the editorial page. How relevant that is in these days of “fake news.”

He got fired eventually. At the time, he owed money to a bunch of friends and since he’d lost his job, he decided to rob a bank in Texas. He entered the bank with a tear gas gun and a .22 pistol. The tear gas gun didn’t fire, so he fired the .22 in the air three times. He was apprehended before he could get away, and because of the gunshots, was imprisoned for armed robbery.

One of Patterson’s former students had been Pierre Salinger; Pierre had been the editor of The Lowell, the school newspaper. Pierre went on to become President Jack Kennedy’s press secretary.

From jail, Patterson got in touch with Pierre, who got Kennedy to issue a pardon and he got out of jail. The athletic director at Stanford gave Patterson a job on the campus. I’m so sorry I never went to thank him in person for his guidance.

Sports

Football

I’d played football in my neighborhood in earlier years, but for some reason didn’t go out for high school football until my last year.

I wasn’t successful. For one thing, all the other guys had two or three more years of high school experience than I did. For another, the football coach was also the swimming coach, and he didn’t want me playing football.

I wanted to play halfback — I knew I could run and catch passes from neighborhood games — but the coach made me play defensive halfback. The first time at practice, our 220 lb. fullback George Schwarz broke through the line and was charging towards me. I weighed 150, and decided then and there I wasn’t going to put my head down and tackle him. Law of physics, or self-preservation. I didn’t get to play too much that season.

In later years, I was glad I wasn’t the football star I aspired to be, as I saw all my football friends suffering years later from the contact aspect of the sport — something that wasn’t noticeable in younger years.

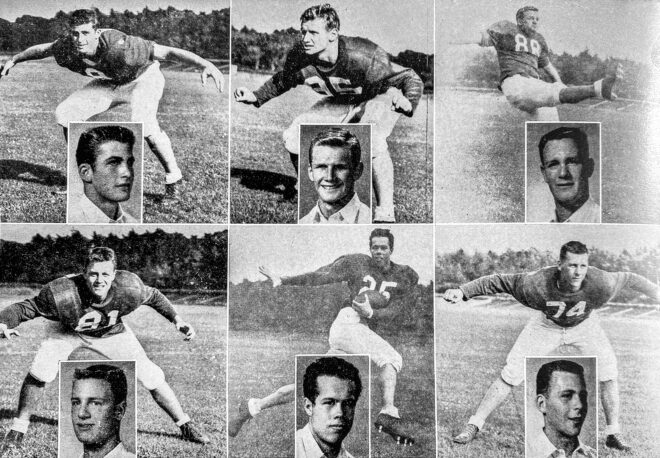

The 1952 Lowell football team, which ended up with four wins and five losses. The highlight of the season was an upset of favored Washington, 6–0, on a second quarter pass from quarterback Pete Kistler to wide receiver Gary Friedman.

But a couple of good things came out of football:

- Each night after practice at the polo fields in Golden Gate Park, we had to run around the ¾-mile track in full gear. I did it faster than anyone else, and it led me into going out for cross-country and then running the half-mile on the track team.

- On the bus to and from practice I started sitting next to Gary Friedman, a star wide receiver. Gary liked me, even if I wasn’t playing football at his level. He “adopted” me, in a sense.**Looking back, I can see that at various times in my life, people have “adopted” me. It happened again at Stanford, and a number of times in the publishing business — people who for some reason liked what I was doing and helped me move along through life.

Swimming

I was on the swimming team — diving during 10th grade, the 100-yard butterfly my last two years. I was on what they called the 130s, a team for lighter weight, smaller guys and I got first place in each event. But it wasn’t the same as varsity swimming.

Track

Bob McGrouther and I were the school half milers. Bob was 6′4″, and the track coach said I took 3 steps to every 2 of Bob’s. Bob was consistently faster than me. My best times were 2:06 in the half mile, and 4:53 in the mile. Good, not great. (Bob ran the half mile in 2:03 and a sophomore, Pete Ryder, ran the mile in 4:45.)

Bob McGrouther and I were the school half milers. Bob was 6′4″, and the track coach said I took 3 steps to every 2 of Bob’s. Bob was consistently faster than me. My best times were 2:06 in the half mile, and 4:53 in the mile. Good, not great. (Bob ran the half mile in 2:03 and a sophomore, Pete Ryder, ran the mile in 4:45.)

(These were years when you didn’t have to concentrate on one sport, as nowadays.)

My three best friends, the guys I hung out with, went to parties with, had adventures with turned out to be Gary, John Brazier, and Ron Chapman.

The 1952 Lowell track team, which was second in the city meet.

Second row up, 5th from left: John Brazier;

Third row up, 7th from left: Lloyd;

8th from left: Gary Friedman; Fourth row up, 2nd from right: Bob McGrouther.

Gary Friedman

Gary said we were half-breeds; both with Jewish fathers, his mother Irish, mine Welsh. His uncle, Max Friedman owned the Fairfax Town and Country Club, which had a big pool surrounded by grassy fields in Marin County. There would be maybe 100 people there on weekends, swimming, lying in the sun, playing volleyball.

Gary said we were half-breeds; both with Jewish fathers, his mother Irish, mine Welsh. His uncle, Max Friedman owned the Fairfax Town and Country Club, which had a big pool surrounded by grassy fields in Marin County. There would be maybe 100 people there on weekends, swimming, lying in the sun, playing volleyball.

Gary and I had a few tumbling routines we’d do on the grass. I’d face him and he’d cup his hands; I’d step into them and he’d flip me up in the air and I’d do a back flip. We also had a trick where I’d climb up and stand on his shoulders.

We started going to parties together, he got me into the “Kappas” fraternity, composed mostly of the top jocks, we’d go to movies and get late night pizza, and so my last year I was hanging out with the cool kids and going to the cool parties.

He got a football scholarship to Arizona State. After he got out of college and the army, he went to work for IBM and became their top salesman one year. We had lunch together in San Francisco in the mid-60s, after I’d adopted what most people would call a hippie lifestyle. He had founded Itel Corporation, a huge equipment leasing company, with trucks, steamships, and planes. His annual salary was reported in the San Francisco Chronicle as being over $200,000, and that was 50+ years ago.

John Brazier

John and I ran cross country. The official course was 1⅞ miles in Golden Gate Park. John had a friend, Walt Boehm, who ran for the Olympic Club, and he taught us the Swedish method of training called fartlek, which consisted of three speeds: you start out running slowly, then shift into moderate speed, then high speed. You’d pick a landmark like a tree to sprint to, then go through the process again. We did this in Golden Gate Park after school. I ended up being 10th in the city meet; John was 15th.

John and I ran cross country. The official course was 1⅞ miles in Golden Gate Park. John had a friend, Walt Boehm, who ran for the Olympic Club, and he taught us the Swedish method of training called fartlek, which consisted of three speeds: you start out running slowly, then shift into moderate speed, then high speed. You’d pick a landmark like a tree to sprint to, then go through the process again. We did this in Golden Gate Park after school. I ended up being 10th in the city meet; John was 15th.

John had a way with people. He was personable, likable, and outgoing. We’d go into department stores and he’d soon be old buddies with the sales clerks. If he was with you, he was with you. Complete attention. Plus he was good looking; girls loved him. And vice versa.

One afternoon he drove us up the famous Lombard winding hill (which is one way going down) in his 1948 Plymouth sedan.

John ended up becoming a lumber baron and living in Seattle. At one point he built a 35-million-dollar sawmill. We were opposites politically, environmentally, and economically, but we still had the same connection. He’d call me up every once in a while and lead off with reference to a stunt we’d pulled together in high school.

He died of pancreatic cancer in 2009, hard to believe for such an athletic guy. Just before he passed away, I told him I loved him. Guys our age don’t tell other guys things like that, so it was special, and we both felt it.

I’ve found with both high school and college friends that, in spite of different ideologies developed in post-high school years, there’s still the bond from the past — which I value. I still go to reunion lunches each year with high school friends, most of whom will be 89 (in 2023). Our numbers are dwindling.

Ron Chapman

Ron was a natural athlete. A swimmer in high school, later he was on a champion Navy swim team, as well as a boxer in the Navy. He became a helicopter pilot and when he got out of the military, he ran marathons. He was one guy that would do anything. He had no fear. If I said, “Let’s jump off this cliff, Ron,” he’d do it.

Ron was a natural athlete. A swimmer in high school, later he was on a champion Navy swim team, as well as a boxer in the Navy. He became a helicopter pilot and when he got out of the military, he ran marathons. He was one guy that would do anything. He had no fear. If I said, “Let’s jump off this cliff, Ron,” he’d do it.

Ron and I hung out after graduation, while I was making up grades to get into Stanford. We went to movies, to the beach, to the RussianRiver.

Ron was the third of my high school friends to do well in the business world. He married a Lowell girl, Nan Figel, and he ended up running a very successful equipment leasing company in Redwood City. We see each other twice a year at our Lowell lunches and every five years at our class reunions.

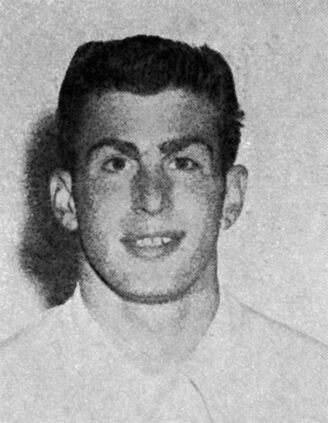

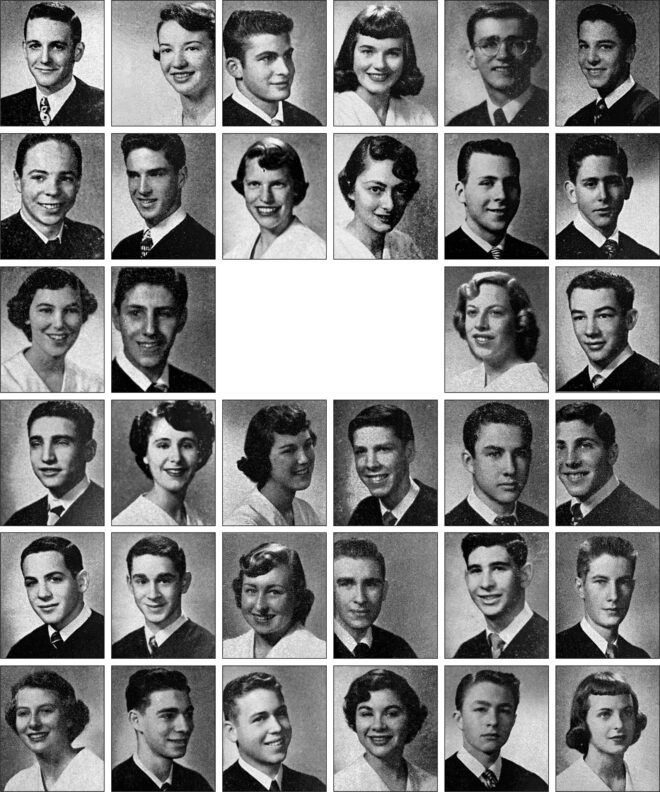

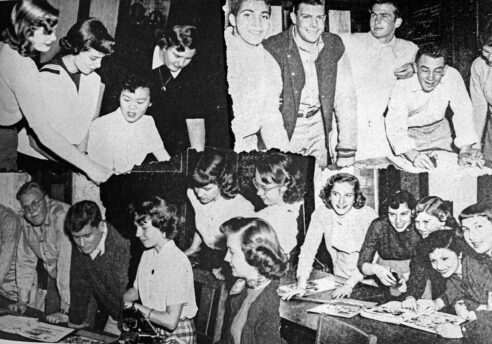

All the photos on these pages on Lowell are from the 1952 Red and White yearbook. They are copies of printed copies, so therefore not of high quality (shot with my iPhone 11 Pro Max).

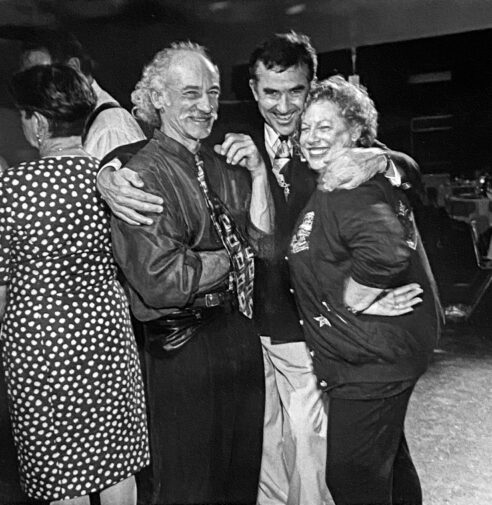

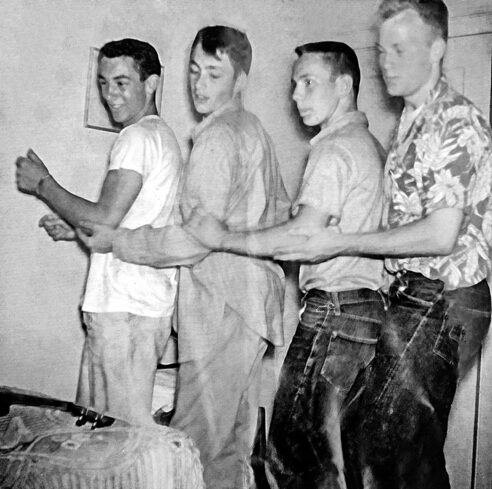

Date night, left to right: John Brazier (partially obscured), Bobbie Debs, Roz Schwartz and Don Kahn, (high school sweethearts who were married for 68 years until Don passed away in 2022 — and ended up with seven great grandchildren), Mike Barnato (who was heir to the Kimberly diamond mines), Carol Berger, Lloyd, Bobbie Brazier

Random photos of our 250-member class. How happy we look! We didn’t realize we were living in one of the most beautiful cities on the planet. (California had 11 million people in 1952 — now there are 40 million.) What a wonderful world we grew up in. We were optimistic. We had no idea things would turn out as they have.

The Uncalled Four

I played the ukulele, a small Martin, which I’d refinished, and I made a “gut bucket,” or washtub bass. In my senior year, four of us formed “The Uncalled Four” and sang at dances and rallies. We did mostly songs from the ’20s and ’30s like “When You Wore a Tulip,” “Peg ’o My Heart,” and “Bye Bye Blackbird.” We also did the a cappella barbershop song, “Goodbye, My Coney Island Baby.”

One of our members was Bill Bixby, who went on to TV fame and fortune as an actor. He appeared in over 80 television shows, including My Favorite Martian, The Courtship of Eddie’s Father,” and The Incredible Hulk. He was in nine movies, including Irma La Douce and Clambake with Elvis Presley.

Bixby’s first TV appearance was at KPIX in San Francisco when our group performed one afternoon in 1952.

Jail Time

Well, sort of. One weekend, after we had graduated, my friend Ron Chapman and I went up to the Russian River for the weekend in his 1948 Ford convertible. We went swimming during the day, and Saturday night we went to Rio Nido, the River’s party town.

As luck would have it, a sheriff’s car came up behind us with flashing lights and pulled us over. When they discovered a six-pack of Country Club malt liquor (unopened) in the back seat, they put us in the drunk tank of the Santa Rosa county jail, along with a bunch of winos, but (luckily), no serious criminals). A depressing experience: horrible food and one seatless toilet for the dozen or so occupants.

We spent Friday night, Saturday, and Sunday there until a judge let us out on Monday. I guess the sheriff’s heavy-handed approach was meant to teach us a lesson, and it did. The experience made me vow to stay out of jail.

When we got home, Ron and I walked into my house. I started out lying to my mother about where I’d been, but she already knew — she’d been called by the sheriff. She was mad as a hornet and started yelling at me, at which time Ron quickly zipped out the door.

Cars

Californians have a special relationship with cars. As a teenager, I was champing at the bit. I got my learner’s permit when I was 14, and pestered my dad for driving lessons. Most of my learning was done on dove hunting trips in the Sacramento Valley with him, driving a green 1946 Willy’s Jeep Station Wagon.

When I turned 16, I was allowed to use my mom’s 1946 Dodge two-door sedan on occasional dates. When I graduated, my dad gave me a 1939 Pontiac convertible (with bucket seats in the back) that he got for $200 from a used car dealer friend. I put twin spotlights on it and drove it too fast and burned out the motor.

My next car, which I had throughout college was a 1947 Chevy 2-door sedan with a 3-speed vacuum shift. When I got into surfing I bought a 1936 Buick 4-door sedan for $35 and sawed a hole in the roof so we could carry surfboards (which stuck up through the roof). The next year I got a 1931 Ford Model A with a rumble seat for $25.

The cars go on and on, but I digress. (My brother has had about 75 cars.)

Fake IDs

I made fake IDs in high school. I would switch numbers on a driver’s license so that the birth date made us 21. I sold them for a couple of dollars each.

This way we could go to nightclubs. Our favorite spot was the “Say When” club on Bush Street, and my drink at that time was a sloe gin fizz.

We saw Harry the Hipster perform there, singing “Get Your Juices at the Deuces” and “Who Put the Benzedrine in Mrs. Murphy’s Ovaltine?” We felt pretty cool, 17-year-olds rushing in where only 21-year-olds dared to tread.

We went a few times to the Arabian Nights, a strip club in the International Settlement; it seemed naughty and exotic to us bumpkin teenagers. This was in the days of Tempest Storm and Blaze Star, strippers who now seem artistic and downright classy in the porn era.

After Graduation

Upon high school graduation, I applied for Stanford and Cal. I was accepted at Cal, but not Stanford (which I had my heart set on). My mom, undaunted, went down to Stanford, and talked the Director of Admissions into admitting me if I made up grades in algebra and chemistry. (I had a B-minus grade average in high school; these days, even straight-A students aren’t assured of being admitted to Stanford.)

Our 40th Reunion: In 1992, we went back to the old Lowell for our 40th reunion (which we’ve done every 5 years). (The school had moved to another location in 1962.) We had a catered dinner in the theater, a band of elderly musicians playing music of the ’40s, and reminisced while roaming the halls and classrooms. It was totally fun, the highlight of all our reunions. It made us realize how special our class was, and what a unique school this was.

I have my Mom’s Lowell class photo from 1948. What a treasure. Thank you for writing this.